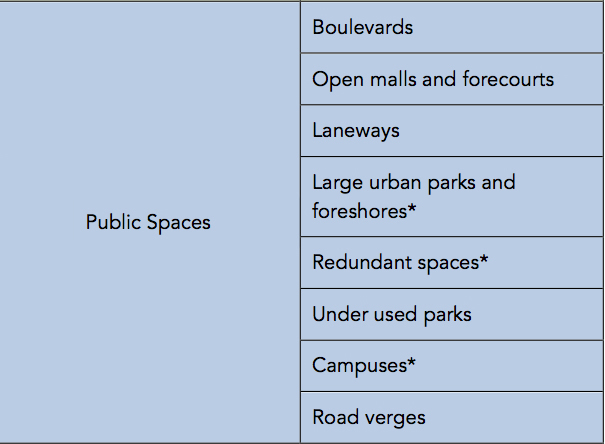

Blog 4 – Categories of Public Spaces

/Below is the figure showing my categories of Public Spaces.

* Parts of some of these large can emerge as claimed places and coastal and foreshore nodes are generally planned to be places within broader foreshore spaces.

As noted in by first blog, public spaces are typified by being frequently used by passer-byer’s who don’t really have a sense of ownership and there is a very weak sense of private geography.

Please note that all photographs are taken by me, unless otherwise attributed.

Boulevards

I’ll start with a quote from the Green Day song “Boulevard of Broken Dreams"

“I walk a lonely road

The only one that I have ever known

Don't know where it goes

But it's home to me and I walk alone

I walk this empty street

On the Boulevard of Broken Dreams

Where the city sleeps

And I'm the only one and I walk alone”

Modern boulevards may best be described as ‘unlonely’ streets where pedestrians dominate and the adjacent land uses are both destinations and aesthetic attractions. The primary purpose of the pedestrian-way is to allow transit rather than being places to stop and do things. The adjacent land uses are what draws people to the boulevard, and both length and variety add to the attractions.

Many boulevards run along foreshores with the water body a significant aesthetic attraction (Figures 1 and 2). Others run through the middle of the city and may have open space (parks) adjacent to the pedestrian way (Figure 3 and 4).

Fig 1: Popular water front boulevard in Porto, Portugal

Fig 2: Barangaroo Headland Park, Sydney Harbour.

Fig 3: Boulevard in the middle of Athens

Fig 4: View of the Washington Mall

Some boulevards have commercial land adjacent to the pedestrian-way – for example cafes, galleries and other tourism related businesses (Figures 5 and 6).

Fig 5: Darling Harbour (Sydney) at night showing the various cafes adjacent to the pedestrian way

Fig 6: Southbank in Melbourne

Walking is the most popular activity, but in the early mornings and late afternoons, running, cycling and other fitness activities are popular (Figures 7 and 8).

Fig 7: Early morning runner on the circular boulevard in Lucca Italy

Fig 8: Early morning exercisers, Swan River Perth.

Whilst these boulevards attract a lot of people, many are occasional users and tourists, which makes the development of sense of place less likely.

In summary, boulevards are popular long pedestrian ways, with limited senses of place, that allow transit and exercising rather than being places to stop and do things, with the adjacent land uses, often including linear waterways, cafes and parklands, drawing people to the boulevard.

Open malls and forecourts

I have grouped these two together because there are strong commercial motivations around the creation of these spaces.

In some ways, open malls are short versions of boulevards. They are typically closed off roads with retail shopping outlets on both sides. The primary purpose of these spaces is to attract people and to enhance the shopping experience (Figures 9 and 10).

Fig 9: Rundle Mall in Adelaide

Fig 10: Burke St mall, Melbourne

Most malls have infrastructure that add to the aesthetics and usability of the space which encourage users to spend time in the mall, for example seating (Figure 11) or public art (Figure 12).

Fig 11: Playground in Manly shopping mall

Fig 12: Public art in the Launceston shopping mall

These spaces are generally popular, but most people stay for only short periods of time, and the regular visitors are those who work in the city.

Forecourts are generally created in the front of large buildings and are technically private spaces –i.e. within private property - but they are permanently open to the public. The owners often create rules about how the space can be used (Figure 13). This sense of private control works against any sense of place developing. Because these are private spaces, the owner can hold their own events – Figure 14 shows a statue of Marilyn Monroe temporarily located in the forecourt of a tower in Chicago

Fig 13: Central Park tower forecourt in Perth, with a sign displaying the ‘rules’ of entry

Fig 14: A statue of Marilyn Monroe temporarily located in the forecourt of a tower in Chicago

In summary, open malls and forecourts are created spaces with a strong commercial basis for their existence – either in support of retail shopping or as publicly available but privately regulated spaces within the boundary of a large building. This primary, non-public, purpose for these spaces works against the development of any sense of place despite their popularity.

Laneways

These are public spaces in that they are, or were, roads. They tend to be narrow and function as pedestrian ways as well as for cars. In some of the older parts of cities like Perth, lanes were used to service houses, for example, the removal of human waste. Figure 15 below shows and old back lane in North Perth. Many laneways in city CBDs have been converted into commercial areas, mostly with cafes and street dining (Figure 16), in part in response to safety concerns – increasing human activity increases surveillance and reduces the safety risk.

Fig: 15: Back lane in North Perth

Fig 16: Commercialized laneway in Christchurch, New Zealand – in this case outdoor seating for a small pub

The undeveloped laneways are primarily about pedestrian movement from one location to another, often being short cuts, and have very limited senses of place. The commercialized laneways, whilst being much more interesting spaces, and more popular transit-ways and destinations, become destinations by acquiring public space and making it private – I have called these’ acquired non-places’, and I discuss these in detail in my next blog.

In summary, laneways are narrow roads, often found in the older parts of cities, whose primary purpose is as pedestrian transit-way, and many CBD laneways have become developed for commercial purposes, thus increasing their popularity and becoming destination spaces as well.

Large Urban Parks and foreshores

These are the large pieces of open space that are largely undeveloped, have low visitor numbers, and usually have a specific purpose not necessarily supporting place making. As noted in my previous blog, certain high user areas within these spaces, usually with supporting infrastructure, can be become acquired places – for example coastal nodes. In WA, we are lucky that the coast – the beach and nearby foreshore areas – are contained within public reserves. Certain locations within these reserves are developed as coastal nodes with the remainder largely remaining undeveloped. These undeveloped areas are mostly fenced off to protect the vegetation, and usually have paths and formal tracks that go through them to allow pedestrian and cycling access (Figure 17). In other locations, the foreshore is narrower with little, if any, vegetation, and the surrounding land uses are residential and open space (Figure 18).

Fig 17: Path in the coastal foreshore between Coogee and Woodman Point south of Perth

Fig 18: Foreshore in Brighton, near Adelaide

The beach is accessible to the public.

Thus, the primary purpose of these areas is conservation or open space, with supporting passive recreation. In some sense, these foreshore areas are like passive boulevards with the land uses adjacent to the path being conservation, open space and/or residential, and the land uses adjacent to the beach are conservation or open space, and the ocean.

Large urban bushland reserves have the same qualities, without the ocean as an adjacent land use (Figure 19). Many large, poorly designed town squares and large inner city parks also come under this category as they simply serve as a pedestrian transit-ways or have poor visitation rates (Figure 20).

Fig 19: Kings Park in Perth

Fig 20: City park in Darwin

There is an argument that some of these places can develop a clear sense of place, exactly because they are not well visited, as they have a sense of wilderness, or people feel a sense of aloneness. This is particularly true of some urban beaches (Figure 21). I will stick my neck out here and say that this sense of personal aloneness is about the space being acquired for a private, not public, use. The sense of place is, therefore, an acquired private sense of place and not a shared public sense of place. Similar to isolated beaches, people can find locations within large, not well used, town squares and city parks for quiet contemplation and to find a sense of aloneness (Figure 22).

Fig 21: Someone finding a sense of wilderness or feeling a sense of aloneness on an isolated urban beach

Fig 22: Someone finding a feeling a sense of aloneness in a large urban park in Porto, Portugal

In summary, large urban parks and foreshores are large spaces with low relatively visitation rates whose primary purpose is other than providing opportunities for place-making. They have features (beaches) of infrastructure (paths) that allow for pedestrian transit, but little opportunity is created for developing a public sense of place, although remote locations within these spaces may allow for an acquired private sense of place associated with aloneness to develop.

Redundant spaces

Redundant spaces are simply those spaces that are neglected, left undeveloped and have little, if any, function. A power line easements is one such space (Figure 23), and another are awkward pieces of green space created when road alignments are changed at intersections (Figure 24)

Fig 23: Powerline easement

Fig 24: Green space created in the front of houses when the road was realigned furrier away from the houses

Some medium strips fall under this category as well (Figure 25). In some cases, these spaces evolve through changing urban and street design where roads and paths become unused as new construction blocks the flow of the path (Figure 26).

Fig 25: Largely functionless medium strip in Leura

Fig 26: A road in Lucca Italy that has been blocked and is now redundant

Under used parks

These are small to medium sized parks that, well, let’s be frank, are poorly designed, do not meet the needs of potential users, and are underused. They are can be those designed and built by developers to ‘market’ the development to a particular demographic – for example young families – but the suburb has outgrown that design (Figure 27). They can also be too small for any practical use with few if any infrastructure (Figure 28)

Fig 27: Underused park in Dunsborough WA. Well designed but not suited to the demographic of the suburb

Fig 28: Small park in South Fremantle with no useable infrastructure

Campuses

These are large tertiary institutions that are too large to be fence off and access controlled, and the main population that accesses them are students. Their grounds and open spaces can be extensive, but there is both a ‘privateness’ and ‘temporariness’ about them (Figure 29). Any member of the public can access these spaces, but it is largely not encouraged and, thus, the sense of ‘privateness’. The key users are, for the most part, only there for short periods of time, and, whilst some sense of place may develop, it is soon lost once students graduate. Some of the spaces and courtyards of buildings and have a stronger sense of ‘privateness’ (Figure 30).

Fig 29: TAFE campus in Adelaide

Fig 30: More private open space in Sydney University

Interestingly, some universities are putting a lot of effort into landscaping an adding infrastructure, with the aim of creating a stronger sense of place so as to encourage students to be on campus more often and longer (Figure 31).

Fig 31: Hammocks provided at Curtin University as a way to add to the sense of place

Road verges

A road verge is different from a street verge in that sense of place develops in streets verges because pedestrians stop and spend time in the street, whereas a road verge is simply a pedestrian transit way. Figures 28 and 29 in my last blog shows the differences between a street and road verge – shown below as Figures 32 and 33.

Fig 32: A typical neighbourhood street showing good connections between the house and the verge and the presence of a footpath – a street verge

Fig 33: A verge in a different neighbourhood with poor connection between the house and the verge and the absence of a footpath – a road verge

Below are some more examples of road verges.

Fig: 34: Narrow road verge – the Causeway in Perth

Fig 35: Road verge in inner Brisbane

Fig: 36: Road verge in Chicago

Fig 36: Very narrow road verge in Florence